Appendix B: Shell Basics

Performing basic operations in the shell—such as navigating your filesystem, managing files and folders, copying and pasting text, and getting help—can be a bit daunting at first. This appendix is a quick-start guide to build your confidence with these tasks.

You can skip this appendix if you're comfortable running a shell, if you know what Bash is, and if you can run basic commands like ls and cd.

Navigating Your Filesystem

Switching from a graphical user interface (GUI) to the shell can take some getting used to. We'll start by taking a look at how to navigate your filesystem and get information on files and folders using the shell.

This section will introduce the pwd, ls, pushd, popd, and cd commands, as well as the related concepts of directories, stacks, and paths. To follow along, make sure you've downloaded and installed the Effective Shell samples and tools by running this command:

curl -fsSL effective.sh | bash

Note that the exact output you see will differ slightly from mine to reflect your user and system information.

Identifying the Working Directory

When you open a folder in a GUI, you can see its contents and interact with them (for example, by copying or moving files). In the shell, the same principle applies: you're always working in a specific folder or directory. This is the working directory, and any command you type will run here unless you specify otherwise.

To find out your current working directory, use the pwd ("print working directory") command:

$ pwd

/home/dwmkerr

Your output may be formatted slightly differently depending on your operating system.

Listing the Contents of the Working Directory

In a GUI environment like the folder system on Windows and macOS, files and folders in the current directory are normally represented as icons. In the shell, you don't have this graphical view, so instead you use the ls ("list directory contents") command to see the files and folders in your working directory:

$ ls

Desktop Downloads fontconfig Pictures Templates

Documents effective-shell Music Public Videos

Again, you'll see different files and folders specific to your system.

Commands like ls and pwd can be combined with options that modify how they work. For example, using the -l ("long") option with ls lists the directory's contents with some extra detail:

$ ls -l

total 40

drwxr-xr-x 2 dwmkerr dwmkerr 4096 Apr 2 19:18 Desktop

drwxr-xr-x 2 dwmkerr dwmkerr 4096 Apr 2 19:18 Documents

drwxr-xr-x 2 dwmkerr dwmkerr 4096 Apr 2 19:18 Downloads

drwxr-xr-x 13 dwmkerr dwmkerr 4096 Apr 3 18:02 effective-shell

drwxr-xr-x 2 dwmkerr dwmkerr 4096 Apr 3 14:07 fontconfig

...

Adding the -l option indicates that you want more information than just the filenames and folder names, such as who owns the file or folder and when it was last modified. Many GUIs have a similar option.

Changing the Directory

To move to a new directory in the shell, you run the cd ("change directory") command. Here I move to my pictures folder within the effective-shell folder:

$ cd effective-shell/pictures

My working directory is now /home/dwmkerr/effective-shell/pictures, which I can confirm by running pwd again:

$ pwd

/home/dwmkerr/effective-shell/pictures

Another common operation is to show all of the files in a directory, including any hidden files. In Linux systems, any file that starts with a dot is considered a hidden file and normally isn't shown when you list the contents of a folder or view the folder in a GUI.

To list all of the files in a folder, including hidden files, you use the ls command with both the -l option and the -a ("all") option. Here I list all of the files in my pictures folder:

$ ls -al

total 2364

drwxr-xr-x 2 dwmkerr dwmkerr 4096 Apr 3 16:43 .

drwxr-xr-x 12 dwmkerr dwmkerr 4096 Apr 3 18:42 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 dwmkerr dwmkerr 1899165 Apr 3 16:43 laos-gch.JPG

-rw-r--r-- 1 dwmkerr dwmkerr 504568 Apr 3 16:43 nepal-mardi-himal.jpeg

-rw-r--r-- 1 dwmkerr dwmkerr 61 Apr 3 16:43 .notes

The -a option tells the ls command not to hide files that start with a dot. As you can see, my pictures folder contains a hidden .notes file, as well as two special folders that I'll describe in the next section.

You might notice a pattern here: shell commands are typically very short, making them easier to enter quickly, and they're often made up of the first letters of the description of their purpose.

Options, Parameters, Flags, and Arguments

You've seen two options so far: the -l and -a options for the ls command. Options are sometimes referred to as flags, parameters, or arguments. In most cases—and in this book—the terms are used interchangeably, although flag generally means a simple option you can switch on or off. Don't worry too much about which word is used; they all just refer to ways you can modify a command's default behavior.

Returning to the Home Directory

The home directory is a special folder where a user can keep their personal files, apart from the system files or files shared by all users.

In most systems, every user has their own home directory, and the contents of this directory are accessible only to that user. Generally, you can't see the contents of another user's home directory (unless you're a system administrator who updates the security settings to allow this, which would be very unlikely in practice). When you open a shell, it starts in the home directory by default. In most of the examples you've seen so far, my working directory has been my home directory, /home/dwmkerr.

You'll likely use your home directory a lot since that's where most of your personal files will be. You can always move back to your home directory, no matter where you are, by running the cd command without any parameters. There's also a special shorthand you can use for it: the tilde (~). For example, I could shorten the command:

cd /home/dwmkerr/effective-shell

to this:

cd ~/effective-shell

As you can imagine, using the tilde shortcut can save you a lot of keystrokes over time.

Now that you can move around to different folders, let's talk a bit about how paths work.

Using Absolute and Relative Paths

A path is the location of a file or folder within the filesystem structure. There are two types of paths: absolute and relative.

An absolute path gives the exact location of a file—for example, /home/dwmkerr/effective-shell. Absolute paths always start with a slash. The first slash represents the root of the filesystem, or the single folder that every other folder lives in. If you come from a Windows background, you might be used to drives, such as c:/ or d:/, instead of roots. On Linux, all files and folders live within one single root folder.

A relative path is expressed in relation to your current working directory, rather than the root, and does not start with a slash. For example, the relative path of a file in the /home/dwmkerr/effective-shell/pictures folder would be effective-shell/pictures/laos-gch.jpg.

If I wanted to move into my pictures folder from a working directory other than my home directory, I would use an absolute path:

$ cd /home/dwmkerr/effective-shell/pictures

If I were already in my home directory (/home/dwmkerr), I could use a relative path instead:

$ cd effective-shell/pictures

As a rule of thumb, use relative paths to save yourself some typing when you want to move to a location within the current working directory. Use absolute paths when you need to move to somewhere completely outside your current working directory.

Moving Around Efficiently

You can use a few tricks to speed up your navigation and quickly move to particular directories.

Navigating with the Dot and Double-Dot Folders

When you combine the ls command with the -a and -l flags to list all the contents of a folder in detail, you'll see two extra entries in the output: . (a single dot) and .. (two dots). These are two special folders that are added by the system but are typically hidden. Let's see how they work.

First, I'll list all of the files in my effective-shell folder in detail:

$ ls -al ~/effective-shell

total 52

drwxr-xr-x 12 dwmkerr dwmkerr 4096 Apr 3 19:54 .

drwxr-xr-x 18 dwmkerr dwmkerr 4096 Apr 3 19:54 ..

drwxr-xr-x 2 dwmkerr dwmkerr 4096 Apr 3 19:00 data

drwxr-xr-x 2 dwmkerr dwmkerr 4096 Apr 3 19:00 docs

drwxr-xr-x 3 dwmkerr dwmkerr 4096 Apr 3 19:00 logs

...

Displaying the output in a detailed list reveals the dot and double-dot folders. The dot folder represents the current folder, so in this case it's essentially an alias for the effective-shell folder. The dot folder can be useful because sometimes you'll want a quick way to say, "Right here—the folder I'm in right now!" in a command. For example, to copy the effective-shell folder to the backups folder, I can do the following:

$ cp -r . ~/backups

The cp command is the copy command. The -r ("recursive") option tells the shell to copy recursively, meaning it will copy the given folder and all of its contents. But one thing to note for now is that copying requires you to specify both the source folder and the destination folder. In this case, instead of typing out the full path of the source folder, I've used . to say "copy the current folder to ~/backups."

The double-dot folder is a shortcut to the folder just above the current folder in the file hierarchy, known as the parent folder. You'll use this shortcut frequently. For example, to quickly jump to the parent of the current working directory, you can type the following:

$ cd ..

This command tells the cd command to move "up" to the parent folder.

The double-dot folder can also be helpful to specify paths outside of your current working directory. Say I'm currently in the /home/dave/Downloads folder. I can use this shortened command to move to the /home/dave/effective-shell folder:

$ cd ../effective-shell

This is like saying, "Go up one level to the /home/dave folder, then move into the effective-shell folder."

Because every folder has a dot and a double-dot folder, you can chain these commands together. For example, if I were in the /home/dwmkerr/effective-shell/pictures folder, I could move to /home like so:

$ cd ../../..

This tells the shell to move up three folders from the current working directory.

Going Back to the Previous Directory

The cd command has a special option that lets you quickly go back to the previous working directory:

$ cd -

Running this command again would return you to the working directory where you started.

You can also move to the last directory, second-to-last directory, and third-to-last directory with the commands cd -1, cd -2, and cd -3 (and so on), respectively.

The cd - command only really works to toggle between the directory you were in last and the one you're in now. If you need to go back and forth multiple times between folders or through a history of directories, using pushd and popd is a better option.

Pushing and Popping the Working Directory

You can quickly move from one location to another and back again with the pushd and popd commands. The pushd ("push directory") command moves you to a new folder but keeps a record of your current working directory. This way, you can easily move back afterward, using the popd ("pop directory") command. Let's look at this in practice.

Say I'm in my pictures folder and I want to quickly check my Downloads folder:

$ pwd # 1

/home/dwmkerr/effective-shell/pictures

$ pushd ~/Downloads # 2

$ pwd

/home/dwmkerr/Downloads

$ ls # 3

New-Wallpaper.jpeg

effective-shell.zip

$ popd # 4

$ pwd

/home/dwmkerr/effective-shell/pictures

Let's break this down. First, I show my current working directory with the pwd command (1). Then I "push" the Downloads folder (2) and show my working directory again to verify that I'm now working in Downloads. I use ls to check which files are in this folder (3). Finally, I "pop" back to where I started, pictures, and use the pwd command once again to confirm the move (4).

You might be familiar with the concepts of pushing and popping if you've ever studied computing or programming, but if not, you're probably wondering where these terms come from. They have to do with the directory stack, the structure the shell uses to keep track of your current working directory. You can picture the directory stack as a stack of plates in a cafeteria. You can easily put plates on top of that stack but not in the middle or at the bottom. When you remove plates, you start by removing the top plate, then the next, and so on.

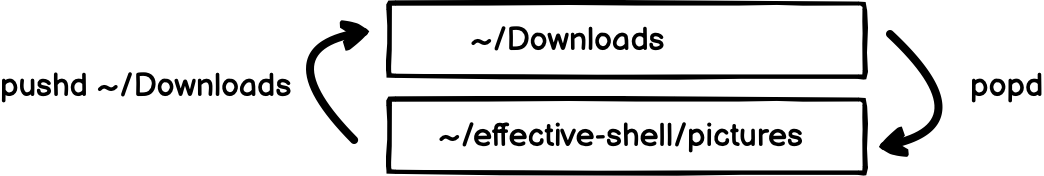

The diagram below illustrates the directory stack for the previous example.

When I used the pushd command, the shell recorded my current working directory (/home/dwmkerr/effective-shell/pictures) and then "pushed" the new location (the Downloads folder) to the top of the stack. Then, when I used the popd command, the shell "popped" Downloads off the top and moved to the location beneath it in the stack, the pictures folder. The item at the top of the stack is always your current working directory.

You can also run pushd without providing any parameters to swap the top two items on the stack. This is a handy trick to quickly switch between two directories you're working in regularly.

Now that you've seen some ways to move around your system more efficiently, let's take a look at how you can manage your files and folders.

Managing Your Files and Folders

In this section, you'll learn how to manipulate files and folders in the shell as you would in a GUI. Once you can organize your files, you'll be well on your way to using the shell more effectively for day-to-day tasks. Here you'll learn to download, unzip, copy, move, rename, and delete files.

Downloading a File

First, you'll download a playground area you can work in to avoid messing with your own personal files as you practice. I've created an Effective Shell playground folder and made it available as a ZIP file at https://effective-shell.com/downloads/effective-shell.zip. You could open a browser, download the file, unzip it, and start from there, but since this appendix is all about how to handle everyday tasks in your shell, you'll do it from the command line instead:

$ cd

$ wget https://effective-shell.com/downloads/effective-shell.zip

--2025-01-18 16:45:37-- https://effective-shell.com/downloads/effective-shell.zip

Resolving effective-shell.com (effective-shell.com)... 185.199.110.153, ...

Connecting to effective-shell.com...|185.199.110.153|:443... connected.

HTTP request sent, awaiting response... 200 OK

Length: 4881890 (4.7M) [application/zip]

Saving to: 'effective-shell.zip'

effective-shell.zip 100%[===================>] 4.66M 1.70MB/s in 2.7s

2025-01-18 16:45:42 (1.70 MB/s) - 'effective-shell.zip' saved [4881890/4881890]

First, using the cd command with no parameters moves you to your home directory. Then, the wget ("web get") command downloads the playground content at the given web address to your working directory. It also shows a progress indicator, which is especially useful if you're downloading a large file.

Not every command is available out of the box on every system. If you get a "command not found" error for wget or any other command covered in this section, install it for your particular system like so (if you're using the Windows Subsystem for Linux, follow the instructions for the flavor of Linux you have installed):

Debian, Ubuntu, Mint:

sudo apt update

sudo apt install -y <command>

RHEL, Fedora, CentOS:

sudo yum install <command>

SuSE, OpenSuSE:

sudo zypper install <command>

Arch/MSYS2:

sudo pacman -S <command>

macOS:

brew install <command>

Cygwin:

setup-x86_64.exe -q --P <command>

Be sure to replace <command> with the missing one when you run this in your shell. If your distribution isn't listed here, check its documentation for instructions on installing packages.

To specify a particular folder in which to download a file, use wget with the -O ("output file") parameter followed by the destination path:

$ wget https://effective-shell.com/downloads/effective-shell.zip -O ~/effective-shell.zip

To check that the file has downloaded, use the ls command with the tilde shortcut and the asterisk (*) wildcard character to see all the ZIP files in your home directory:

$ ls ~/*.zip

/home/dwmkerr/effective-shell.zip

Congratulations! You've successfully downloaded the ZIP file to your home directory.

Unzipping a File

You know this download is a ZIP file because it ends in .zip, but say the extension was missing. To learn more about a file, you can use the file ("determine file type") command with the file location like so:

$ file ~/effective-shell.zip

/home/dwmkerr/effective-shell.zip: Zip archive data, at least v1.0 to extract

The output of the file command will vary based on the type of file. This output tells you that the file is a ZIP archive (a collection of files and folders bundled together into one file for easier sharing) that has been compressed with version 1 of the ZIP format. To extract the files and folders this archive contains, you'll need to unzip it.

First, use cd ~ to navigate to the directory the file is in, which should be the home directory. Then unzip the playground folder with the unzip ("unzip archive") command:

$ unzip effective-shell.zip

Archive: /home/dwmkerr/effective-shell.zip

creating: effective-shell/

creating: effective-shell/data/

inflating: effective-shell/data/top100.csv

...

Running unzip prints the name of each file and folder as it unzips. To check that the folder has been unzipped, use ls to list the contents of the current working directory:

$ ls

...

effective-shell.zip

effective-shell

...

You should see a folder named effective-shell in the list, as well as the effective-shell.zip file you downloaded. This confirms that you've successfully unzipped the playground file and now have a folder named effective-shell containing its contents. You no longer need the ZIP file, so read on to learn how to delete it.

Deleting a File

Now that you've extracted the contents of the ZIP file you downloaded, delete it with the rm ("remove") command as follows:

$ rm ~/effective-shell.zip

If you were to list the contents of the working directory now, you'd no longer see the ZIP file.

Be very careful with the rm command. Unlike in a GUI environment, deleted files aren't moved into a recycle bin where you could still retrieve them if you needed to; they're gone forever. In Chapter 15, you'll see some ways to customize this behavior, but as a rule of thumb, only use the rm command to remove files you want to delete for good.

By default, the rm command deletes only files, so it will fail if you try to delete a folder:

$ rm ~/effective-shell

rm: /home/dwmkerr/effective-shell: is a directory

You'll see how to delete a folder shortly.

You can use the -i ("interactive") flag with the rm command to delete interactively, meaning you'll be shown a prompt for each file in the target directory and offered the option to delete it or not:

$ rm -i ./effective-shell/data/*

rm: remove regular file 'effective-shell/data/top100.csv'?

Notice the use of the wildcard * to find all the file types in the data folder. When the shell asks you to confirm that you want to delete a file, enter y to delete it or n to keep it.

Viewing a Directory Tree

The useful command tree allows you to see a treelike view of a directory and its contents, similar to a GUI representation of a filesystem.

The tree command is not installed on all systems by default, so if you get a "command not found" error message when you try to run it, follow the installation instructions in the "Command Not Found Errors" box above.

Let's take a look at the playground folder:

$ tree ~/effective-shell

/home/dwmkerr/effective-shell

├── data

│ └── top100.csv

├── logs

│ ├── apm-logs

│ │ ├── apm00.logs

│ │ ├── apm01.logs

├── pictures

│ ├── laos-gch.JPG

│ └── nepal-mardi-himal.jpeg

├── programs

│ └── web-server

│ └── web-server.js

├── quotes

│ ├── iain-banks.txt

│ └── ursula-le-guin.txt

...

11 directories, 18 files

I've abbreviated this output for readability, so on your system you'll likely see a lot more files and folders.

If you want more information about a particular file, you can use the file command, as mentioned earlier.

Copying a File

The cp command takes the form:

cp <source> <destination>

where <source> is the name of the file you want to copy and <destination> is the new location and name for the file.

Now you'll try it out to make a copy of one of the files in the pictures folder. First, move to the pictures folder and then list its contents:

$ cd ~/effective-shell/pictures

$ ls

laos-gch.JPG nepal-mardi-himal.jpeg

Then, use cp as follows to make a copy of the loas-gch.JPG photo:

$ cp laos-gch.JPG laos-gch-copy.JPG

You can confirm that you've made a copy by listing the contents of the current working directory:

$ ls

laos-gch-copy.JPG

laos-gch.JPG

nepal-mardi-himal.jpeg

You can use relative or absolute paths for the source and destination files.

Renaming and Moving Files

The mv ("move") command renames or moves files, and like cp it follows the form <source> <destination>. To rename your newly copied image file with the extension .jpeg, run the following:

$ mv laos-gch-copy.JPG laos-gch-copy.jpeg

Then run ls again to see the results:

$ ls

laos-gch-copy.jpeg

laos-gch.JPG

nepal-mardi-himal.jpeg

As you can see, your copied file has been renamed, or "moved" into the same folder under a new name. You can also use mv to move a file to another folder and change its name in one step. Move your copied image file to the tmp folder and change its name again like so:

$ mv laos-gch-copy.jpeg /tmp/climbing-photo-backup.jpeg

You've moved the loas-gch-copy.jpeg file from pictures to tmp and renamed it to climbing-photo-backup.jpeg in one operation.

Copy and Move Tips

You'll see the copy and move commands a lot throughout the book, so let's go over a few tips to make working with them easier.

First, remember that the cp and mv commands both have the basic structure <source> <destination>. When you're copying or moving (renaming) a file inside the working directory, you don't need to provide a destination folder path:

cp file1 file2

mv file1 filenew

The first command makes a copy of file1 in the working directory and names it file2. The second command renames file1 to filenew in the working directory.

If you're copying or moving a file to a different folder, you don't need to provide the new filename unless you want to rename the file; you can just provide the destination folder path:

cp filenew ~/backups

mv file3 ~/backups

The first command copies filenew from the working directory to the backups folder in your home directory. The second command moves file3 from the working directory to the backups folder in your home directory. In both cases, the filename doesn't change because you haven't specified a new one.

When copying a folder, you must add the -r flag to copy the folder and all of its contents; otherwise, only the folder itself would be copied. Here's an example:

cp -r ~/backups ~/backups.old

This makes a copy of the backups folder, including all of its contents, in your home directory and names it backups.old.

The mv command doesn't require the -r flag:

mv somefolder newfolder

This command renames the somefolder folder to newfolder in the working directory; none of the folder's contents are lost.

Finally, remember that you can mix and match relative and absolute paths:

cp -r /home/dwmkerr/backups ./backups

mv scripts/test-script.sh /tmp

In the first example, I'm copying the backups folder from my home directory to my current working directory. The source path (the first parameter) is an absolute path, as indicated by the opening slash, and the destination path (the second parameter) is a relative path that explicitly uses the dot folder.

In the second example, I'm moving a file from the scripts folder in my current working directory to the system's tmp folder. The first path is relative; the second is absolute.

In general, when using these commands, use the form you find easiest to type and understand.

Creating a Folder

The mkdir ("make directory") command creates a new folder. Move back into the ~/effective-shell folder and run mkdir to create a new folder called photos as follows:

$ cd ~/effective-shell

$ mkdir photos

Then run tree like so to see the results:

$ tree -L 1

.

├── data

├── logs

├── pictures

├── photos

├── programs

├── quotes

├── scripts

├── text

└── websites

9 directories, 0 files

The -L ("level") parameter specifies how many levels of folders you want to see. By setting the level to 1, you're indicating that you want to see only the immediate children (subfolders) of the effective-shell folder. You can also see that you've successfully created the new photos folder. Running ls -l would show you that the new photos folder has a more recent date than the others.

Now you'll organize your photos by year and topic. Say you want to create a 2019 subfolder containing an outdoors subfolder, which in turn contains a climbing subfolder, so that you have the folder structure photos/2019/outdoors/climbing. In most GUIs, you'd have to create each subfolder one at a time. In the shell, however, you can create nested folders with a single command:

$ mkdir -p photos/2019/outdoors/climbing

$ tree photos

photos

└── 2019

└── outdoors

└── climbing

3 directories, 0 files

The -p flag means "create intermediate directories," but it's easier to remember as "-p for parent": you're creating the climbing folder and its parent folders as well.

You're starting to see how working in a shell can be more efficient than using your GUI. Now create another set of directories for 2020 climbing photos:

$ mkdir -p photos/2020/outdoors/climbing

$ tree photos

photos

├── 2019

│ └── outdoors

│ └── climbing

└── 2020

└── outdoors

└── climbing

6 directories, 0 files

Notice that mkdir did not delete or replace the photos directory. If you provide the -p flag, mkdir will check whether the parent directories already exist and create them only if need be. If you don't include the -p flag, but the parent directory already exists, the shell assumes you're making a mistake and shows an error.

Creating a File

The purpose of the touch ("create files and set access times") command is twofold: it's used to create a new file without any content and to update an existing file's timestamp, a record of the last time someone opened or changed ("touched") the file. Here's how it works:

$ touch ~/my-notes.txt

This command creates a new, empty file in the home directory called my-notes.txt. If a file by that name had already existed, touch would simply have updated its "last access" and "last modified" times to the current time. You can see the last modified time by running ls -l:

$ ls -l ~

...

-rw-r--r-- 1 dwmkerr staff 1899165 Aug 21 22:20 my-notes.txt

...

The last modified time—which, in this case, is the same as the file creation time—is 10:20 PM on August 21.

Using touch is just one way to create a file in the shell; you'll see many others throughout the book.

Working with Wildcards

A wildcard is a special symbol that represents more than one character. The most common wildcard is the asterisk, which represents any sequence of characters. You've seen it already, such as when you used ls ~/*.zip to find files that end in .zip in your home directory. Now you'll use it to copy all the files from the pictures folder into the photos/2019/outdoors/climbing folder:

$ cp pictures/* photos/2019/outdoors/climbing/

$ tree photos

photos

├── 2019

│ └── outdoors

│ └── climbing

│ ├── laos-gch-copy.jpeg

│ ├── laos-gch.JPG

│ └── nepal-mardi-himal.jpeg

└── 2020

└── outdoors

└── climbing

6 directories, 3 files

Here the * represents everything and anything, so everything from pictures is copied. You can also use wildcards to filter on file type, as you did with *.zip earlier, or to filter on filename, such as l* for any files starting with l (which would match laos-gch-copy.jpeg and laos-gch.JPG but not nepal-mardi-himal.jpeg, which contains two ls but doesn't start with one). You'll learn about other wildcards throughout the book.

Deleting a Folder

The rmdir ("remove directory") command deletes folders. Now that you have your more organized photos/2019/outdoors/climbing folder, you can delete the pictures folder:

$ rmdir pictures

rmdir: pictures: Directory not empty

As you can see, rmdir will fail if the directory isn't empty to prevent you from unintentionally deleting any files or folders it contains. To remedy this, use a wildcard to delete all the files in the pictures folder, then delete the folder itself:

$ rm pictures/*

$ rmdir pictures

The pictures folder has now been deleted. You can also delete the folder and its contents with one single command by using the -r parameter:

$ rm -r pictures

You can use whichever method you prefer. Most people use rm -r as it will delete the folder whether it's empty or not, but I suggest you use rmdir to be certain you don't delete files unintentionally—it gives you a bit of a safety net and reminds you to check the files inside first!

One final folder trick: if you decide you don't want the 2020/outdoors/climbing directory, you can use rmdir -p to remove the empty folder and any empty parents:

$ rmdir -p photos/2020/outdoors/climbing

rmdir: photos: Directory not empty

$ tree photos

photos

└── 2019

└── outdoors

└── climbing

├── laos-gch-copy.jpeg

├── laos-gch.JPG

└── nepal-mardi-himal.jpeg

3 directories, 3 files

This command deleted 2020/outdoors/climbing but stopped at the photos folder because that folder still contains 2019 and its subfolders.

Showing Text Content

The cat ("concatenate") command writes out the contents of one or many text files. This is a handy way to see the text in a file without leaving the shell. For example, the effective-shell playground's quotes folder contains two .txt files:

$ ls quotes

iain-banks.txt ursula-le-guin.txt

Using cat, write out the contents of the ursula-le-guin.txt file to the screen like so:

$ cat quotes/ursula-le-guin.txt

"What sane person could live in this world and not be crazy?"

- Ursula K. Le Guin

You can give the cat command many files, and it will write them all out. To write out all the text from all the quotes files, use the * wildcard:

$ cat quotes/*

"The trouble with writing fiction is that it has to make sense,

whereas real life doesn't."

- Iain M. Banks

"What sane person could live in this world and not be crazy?"

- Ursula K. Le Guin

You can also use the cat command to join, or concatenate, the contents of many files together:

$ cat quotes/* > quotes/all-quotes.txt

This command moves the content of all the quotes files into a single all-quotes.txt file. You can check the folder's contents with tree quotes or ls quotes.

The > is a redirection operator that tells the shell to write to a file instead of to the screen. If the file you're moving the content to doesn't exist, the shell will create it for you. Redirection is a big theme in Part I, and you'll be seeing a lot more of the cat command there as well.

Zipping a File

Earlier you used the unzip command to extract the zipped playground file you downloaded. You've made a lot of changes to the playground folder since then, so you'll finish off this section by using the zip command to zip up the whole folder:

$ zip -r new-playground.zip .

The -r flag tells zip to zip the folder you specify and all of its contents. As its first parameter, the zip command takes the name and location of the file you want to create—in this example, new-playground.zip. Then you pass the files or folders you want to zip. Here, the dot folder specifies that you want to zip the current folder, so make sure you're in the top-level effective-shell folder before you execute the command.

You can also give zip more than one file or folder. To zip both the quotes and the photos folders, run this command:

$ zip -r images-and-words.zip photos quotes

The more you use zip and the other commands I've described here, the more familiar the parameters will become. But if you get stuck, help is readily available. See the "Getting Help" section below.

The Clipboard

Different shell environments and operating systems manage the clipboard in different ways. Being able to quickly copy and paste to and from the shell is essential to using it effectively. This section will explain how the clipboard works on different systems and how to create your own clipboard commands that will work across systems.

Mastering Clipboard Essentials

You're probably familiar with the common keyboard shortcuts to copy and paste content to and from the clipboard: Ctrl+C and Ctrl+V on Linux and Windows, and Cmd+C and Cmd+V on macOS. However, these commands don't work the same way in every shell. For example, here I've tried to use Ctrl+V a few times to paste into a terminal on Ubuntu:

$ ^V^V^V

Instead of pasting the contents of the clipboard into the shell, this key combination has written the characters ^V to the terminal. Why is this?

One reason is historical (the shell has been around for a long time, so you'll see this answer a lot). Using Ctrl in a shell sends a signal—a special command the shell uses to control programs. Specifically, by using Ctrl you're signaling your intention to perform an action rather than enter text with your next keystroke. Most modern operating systems have adopted this convention. For example, Ctrl+S is used almost universally as a shortcut for the save command.

Modern shells tend to follow the conventions established by earlier shells to ensure a consistent experience for users. Both Ctrl+C and Ctrl+V have long had specific meanings in the shell that predate the current copy and paste shortcuts. Using Ctrl+C cancels a running program by telling the shell to send an interrupt signal to the program, which terminates it. You'll see signals again and again throughout the book.

What about Ctrl+V? This is the fancy-sounding verbatim insert command. It tells the shell to write out the subsequent keystroke directly to the screen rather than interpreting it as a Ctrl command. By using Ctrl+V, you can write out special characters like the escape key, left or right keys, and even the Ctrl+V combination itself as in the previous example.

If you type Ctrl+V twice, the shell writes out the text ^V. The caret or hat symbol (^) represents Ctrl. The first Ctrl+V tells the shell to write out the following command, so the second Ctrl+V is written out verbatim, meaning the text representation of the command is displayed.

You can try writing out some different sequences. You'll see various odd-looking symbols for special keys like the Alt key.

Because the shell is already using the keyboard combinations you'd normally use for clipboard commands, you'll need alternatives for those functions. Follow the instructions I've provided next for your particular platform.

Windows

If you're using Command Prompt, then the usual shortcuts will work fine. However, if you are using Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) and Bash, you will need to tweak the configuration.

To set up an alternative, go to Properties > Options, select Use Ctrl+Shift+C/V as Copy/Paste, and click OK. You can now use Ctrl+Shift+C for copy and Ctrl+Shift+V for paste. To select text, hold down the right mouse button and drag over it.

Linux

On most Linux systems, you'll be using GNOME Terminal or KDE's Konsole, which means that you can use Ctrl+Shift+C for copy and Ctrl+Shift+V for paste. To select text, hold down the right mouse button and drag over it, or right-click the text.

macOS

Mac users can just use Cmd+C for copy and Cmd+V for paste. The shell doesn't recognize the special Mac command character, so these shortcuts don't clash with any existing ones. To select text, hold down the left mouse button and drag over it.

Creating Custom Clipboard Commands

Copying and pasting text to and from the clipboard is useful, but you can do a lot more. With a couple of basic commands, you can hugely expand your capabilities and make everyday tasks far easier to accomplish. However, there's one small hurdle to clear first: the clipboard is accessed in different ways on Windows, Linux, and macOS. In other words, there's no standard tool you can use across all three platforms to manage the clipboard.

To address this problem, I'll walk Windows and Linux users through creating two clipboard commands that will work across platforms: pbcopy and pbpaste. If you're a Mac user, you don't need to do anything; pbcopy and pbpaste are built in to macOS.

Windows

Assuming you're using WSL, you'll need to run the following two commands:

$ alias pbcopy="clip.exe"

$ alias pbpaste="powershell.exe -command Get-Clipboard | tr -d '\r' | head -n -1"

Don't worry for now about how these commands work; by the time you've gone through the book, they should make perfect sense.

Linux

On Linux, first you'll install the xclip program and then set up the pbcopy and pbpaste commands to use it:

$ sudo apt install -y xclip

$ alias pbcopy="xclip -selection c"

$ alias pbpaste="xclip -selection c -o"

If you're already confident with how xclip works and want to use it directly, there's no need to run these commands.

For both Windows and Linux, you've used the alias command to create pbcopy and pbpaste. In Bash (and most shells), an alias is a shortcut for a longer command.

You'll need to repeat these instructions every time you close and reopen your terminal. Chapter 15 explains how to make permanent customizations to your shell so that you don't have to repeat this setup.

Copying and Pasting with pbcopy and pbpaste

Now you can use the pbcopy and pbpaste commands to access the clipboard from the shell.

The ~/effective-shell folder contains a text file with the names of some characters from the TV show The Simpsons. Open simpsons-characters.txt in your text editor and copy the following text from it:

Kirk Van Houten

Timothy Lovejoy

Artie Ziff

Then paste it into the shell as follows:

$ pbpaste

Kirk Van Houten

Timothy Lovejoy

Artie Ziff

Rather than copying the text by opening your text editor (which breaks you out of your shell flow), you could use the cat command to write the entire contents of the simpsons-characters.txt file to the screen and then manually select the text and copy it. However, this approach is fiddly and wouldn't be convenient if the file was large and you had to scroll to find text.

Instead, you'll use a pipeline to pass the output of the cat command into the pbcopy command:

$ cat ~/effective-shell/text/simpsons-characters.txt | pbcopy

Now try pasting—you should see the contents of the file.

The | symbol is the pipe operator, which is used to "chain" commands together in a pipeline. Here, the pipe tells the shell to take the output from the command on the left and send it straight to the input of the program on the right. Pipelines are covered in detail in Chapter 2, and you'll see them in use throughout the book.

Getting Help

Being able to access help quickly, without jumping to a browser and disrupting your flow, is one of the most crucial things you can do to become an effective shell user. A wealth of information is available directly in the shell, only a few keystrokes away.

This section will introduce you to the man ("manual") command, the standard help system available on all Unix-like systems. You'll also learn about a useful tool you can install called tldr, which might be more helpful for day-to-day use. Finally, we'll take a look at the cht.sh site for those circumstances when you do need to access a browser for help.

Using the Manual

The man command can help you with tools, commands, and concepts. Most tools you encounter in the shell have manual pages (man pages for short) available.

The most basic way to get help with a command is by entering the command name as the first parameter of man:

$ man cp

CP(1) BSD General Commands Manual CP(1)

NAME

cp -- copy files

SYNOPSIS

cp [-R [-H | -L | -P]] [-fi | -n] [-apvX] source_file target_file

cp [-R [-H | -L | -P]] [-fi | -n] [-apvX] source_file ...

target_directory

DESCRIPTION

In the first synopsis form, the cp utility copies the contents of the

source_file to the target_file. In the second synopsis form, the

contents of each named source_file is copied to the destination

target_directory. The names of the files themselves are not changed.

If cp detects an attempt to copy a file to itself, the copy will fail.

...

This opens the man page for the cp command, detailing all of its command line options and specifics on how to use it. This information can be rather lengthy, but fortunately the shell includes a feature to help you navigate it.

Quickly Checking Parameters

If you just need to check what parameters are available for a command, you can often skip the man page. Simply enter the name of the command followed by a hyphen (-) and then press Tab. Try it out by entering mkdir - and then pressing Tab. You should see the following output:

-m -- set permission mode

-p -- make parent directories as needed

-v -- print message for each created directory

This convenient shortcut gives you only the information you need and thus can be much easier to navigate than a man page.

The Pager

The shell uses a tool called a pager that allows you to use the arrow keys to scroll through content that doesn't easily fit on a screen, such as man pages. In other words, the pager provides the keyboard interface to look through the file.

On most systems, this pager is the less program. These are the most common commands for navigating through files with less:

| Key | Action |

|---|---|

d | Scroll down half a page |

u | Scroll up half a page |

j/k | Scroll down or up a line. You can also use the arrow keys for this |

q | Quit |

/searchterm | Search for the text specified after the forward slash |

n | When searching, find the next occurrence |

N | When searching, find the previous occurrence |

Alternative pagers are available (on many Unix-like systems, you'll have less, more, and most), but in general, less will provide what you need.

Builtins

Sometimes you will look up a command in the manual and get the "builtins" page:

$ man cd

BUILTIN(1) BSD General Commands Manual BUILTIN(1)

NAME

builtin, !, %, ., :, @, {, }, alias, alloc, bg, bind, bindkey, break,

breaksw, builtins, case, cd, chdir, command, complete, continue,

...

This happens when the command you are looking up—cd, in this case—is a built-in shell command rather than a program with a man page. Most shells still offer a way to get help with such commands. For example, Bash has the help command:

$ help cd

cd: cd [-L|[-P [-e]] [-@]] [dir]

Change the shell working directory.

Change the current directory to DIR. The default DIR is the value of

the HOME shell variable.

...

The Z shell doesn't have an equivalent of the help command for builtins. Instead, it has a set of man pages. To get help on builtins, use man zshbuiltins. Type man zsh and press Tab to see a list of suggested topics.

This is all I'll say about help for now, but you'll see it used where appropriate throughout the book.

Manual Sections

In man pages, you'll often see tools listed with numbers after them. Take a look at man less as an example:

$ man less

LESS(1) LESS(1)

NAME

less - opposite of more

...

The number after less is the manual's section, which is used to categorize certain help topics. On most Unix-like systems, you can find the section definitions in the manual documentation by running man man. Here's a snippet of what you might see:

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Executable programs or shell commands |

| 2 | System calls (functions provided by the kernel) |

| 3 | Library calls (functions within program libraries) |

| 4 | Special files (usually found in /dev) |

| 5 | File formats and conventions (e.g., /etc/passwd) |

| 6 | Games |

| 7 | Miscellaneous (including macro packages and conventions) |

| 8 | System administration commands (usually only for root) |

| 9 | Kernel routines (non-standard) |

You can specify which section of the manual to search (for example, if there's an entry in multiple sections) by running the following:

$ man <sectionnumber> <searchterm>

To get more information about a section itself, open its intro page like so:

$ man 1 intro

INTRO(1) BSD General Commands Manual INTRO(1)

NAME

intro -- introduction to general commands (tools and utilities)

DESCRIPTION

Section one of the manual contains most of the commands which

comprise...

In general, you won't need to worry about the section specifics unless you're looking for a tool that has an entry in more than one section or you need to look up the section number that appeared in online or offline documentation for the tool.

Man Page Titles and Summaries

You can search man page titles and summaries like so:

$ man -k cpu

cpuwalk.d(1m) - Measure which CPUs a process runs on. Uses DTrace

dispqlen.d(1m) - dispatcher queue length by CPU. Uses DTrace

gasm(n), grammar::me::cpu::gasm(n) - ME assembler

You can also use the apropos or whatis commands to search through the manuals. However, for simplicity's sake, just remember man -k!

Summarizing Output with tldr

Say you want to compress some files. You know you can do this with the zip command, but you've forgotten the syntax, so you run man zip. The output is extensive—about 30 pages!

Now compare that to this output from the tldr (short for "too long, didn't read") tool:

$ tldr zip

zip

Package and compress (archive) files into a Zip archive.

See also: `unzip`.

More information: <https://manned.org/zip>.

- Add files/directories to a specific archive ([r]ecursively):

zip -r path/to/compressed.zip path/to/file_or_directory1 ...

- Remove files/directories from a specific archive ([d]elete):

zip -d path/to/compressed.zip path/to/file_or_directory1 ...

The first example is exactly what you're looking for. More information is shown later on, and for some more complex details, you might have to go to the manual, but this is great for the basics.

The tldr tool is available on most package managers, including Homebrew and Apt. It's open source and community maintained. You can find instructions for installing it at https://tldr.sh.

Accessing Online Cheat Sheets

One final resource well worth sharing is cheat.sh (https://www.cheat.sh), a fantastic online collection of "cheatsheets" covering tools, programming languages, and more. But its real beauty lies in how it integrates into the shell. To see what I mean, run the following command:

$ curl cht.sh

The curl command, which you'll see again and again, is a tool for downloading content from the web. If you load cheat.sh (or its shortened version, cht.sh) from the shell, you get a text version of the website. You can then look at all sorts of content by following the guide shown.

The cheat.sh website aggregates many data sources—including tldr. This means you can get information on tools without even having to install them locally.

Now that can be a real time saver!